By Obelit Yadgar

From the beginning, the Mesopotamian Nights productions have served a feast of Assyrian musical gems backed by a big symphony orchestra. With new operas performed in Assyrian to ballets danced in dazzling traditional costumes, the musical events have offered something for every taste. All that trimmed with clusters of sweet and sentimental songs by past and present composers.

What a treat to experience the artistic heights the Assyrian performing arts can reach.

The 2013 production promises another musical extravaganza packed with new works and fresh ideas. This year it’s the re-discovery of the Assyrian choir. “The choir is more than just a few people singing together,” says Artistic Director Fred Elieh. “It’s people with different backgrounds, ideas and feelings all becoming one and delivering a melodic message.”

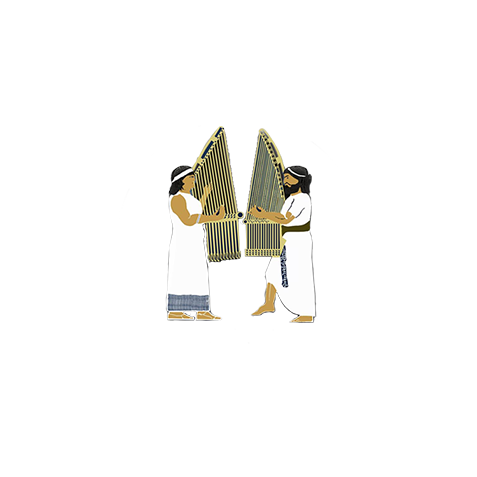

George Somi, the exceptionally talented young Assyrian composer, starts the big works with two movements from his orchestral suite The Assyrian Legacy. The movement titled Hammurabi’s Law celebrates the code of law that is known as the first law code. “The music capitalizes on ancient Near Eastern tones by using the Hijaz Maqam, a scale readily identifiable as Middle Eastern,” explained Somi. “The rhythms are deliberate and vigorous, representing the content of the Law Code.”

The fourth movement, titled The Fall of the Great Empire, represents the fall of Nineveh, in 612 B.C. “The Fall is cinematic and grave,” added Somi.

Noted Assyrian composer the Rev. Samuel Khangaldy offers a wealth of choral works for the 2013 production. Some are original and some arrangements of works by other composers. That included the Mar Benyamin Oratorio, a work written originally for a small choir and piano written by Nebu Isabey. The oratorio recounts the betrayal and subsequent murder of the Assyrian Church of the East patriarch in the 1917 genocide.

Khangaldy has arranged and orchestrated three songs, from old recordings, by Rabi Yacoub Bet Yacoub for solo voice with choir. “‘Girls Look Like Angeles’ and ‘My Beloved Young Man’ are combined into a medley,” said Khangaldy. The third song is “Echo of Wisdom.”

Rabi Yacoub, born in Urmia, Iran, in 1896, was an Assyrian scholar, educator, writer and poet. “His music was very simple and filled with sweet innocence,” he added.

Khangaldy regards The New Mesopotamia, which closes the first half of the program, as his masterpiece. He set it to a poem by the Assyrian writer, poet and educator MarcelJosephson. Khangaldy recalled the words touched his heart and soul so much that he felt compelled to write the music for the poem.

“This is about the new Mesopotamia that calls for her sons and daughters to put all their differences aside and to unite in building a new Mesopotamia, our own homeland,” he explained. “I didn’t have to change any words. Everything about it, from rhythm to syllable, was perfect and I had no problem writing the music.”

French composer Michel Bosc returns to Mesopotamian Nights with a tender and poignant instrumental work titled “The Prayer of Assyrian Nation.” The music is a good lead in the second half of the program into Samuel Khangaldy’s The Marriage Proposal. This charming musical comedy for five solo singers draws a light-hearted picture of life and marriage in an Assyrian village. In spirit, it recalls the bubbly English light musicals of Gilbert and Sullivan.

The musical is an arrangement and orchestration of a song written by the noted Assyrian writer, composer and musician William Daniel, published in the early 1940s. “The whole song as Rabi Daniel wrote it was about four or five minutes long,” Khangaldy pointed out. “I added new music to it and more dialogue to make it about fifteen minutes long.”

The Marriage Proposal serves as a primer in the second half for a celebration of songs made popular by two Assyrian legends: the late Biba and Shamiram. In Iraq, Edward Yousif, known as Biba, was called “King of Singers.” Assyrians loved him, for his music served as the reflection of their lives: the joy, the love, the suffering.

Biba said he and his musical collaborator George Ishu were always looking for a new sound, something never heard before by Assyrians. “We did not want to imitate Western music,” he said. “We wanted to continue in the path of Eastern music, but posses a new sound, provide a new dimension.”

Shamiram Urshan, in neighboring Iran, was already a song and dance artist by age eight. She was born in Tehran, where she explored the wide spectrum of the performing arts. Even after immigrating to the U.S. and settling in Seattle, Washington, with her husband, and even during the years she raised her three children, Shamiram remained the consummate Assyrian song and dance artist.

She turned professional singer when her children were grown up. That she had a wealth of Assyrian songs in her treasure chest already, songs written by her late father Daniel Gevargis Urshan, her career soared internationally. Her first album, recorded in 1978, was a major hit among Assyrians worldwide.

“We will have four different Assyrian singers singing nine of their songs,” said Artistic Director Fred Elieh.

The popular Assyrian artists George Gindo, Avadis Sarkissian, Stella Rezgo and Rita Toma Davoud will romp through nine of Biba and Shamiram songs. George Somi and Devin Farney have arranged all the songs. The music of each artist will be preceded by a short biographical documentary.

“We have not even started utilizing the wealth of Assyrian talent out there,” noted Mesopotamian Nights producer Tony Khoshaba. “Not even explored the musicians from Western Assyria — commonly known as the Jacobites — tradition.”

The biggest challenge still remains, Khoshaba admitted, and that is to expand the audience beyond the Assyrian community and taking Assyrian arts to the mainstream. “We need to figure out how to do this,” he added. “We have created enough material that could be appealing to people outside our community.”

With a string of successful musical gems from Mesopotamian Nights, as well as much needed support from Assyrians proud of their culture and artistic heritage, Khoshaba’s dream can only be just around the corner. It takes vision to realize the potential in the Assyrian performing arts. It also takes willing hands to throw open the curtain and watch them soar.