Give Assyrians a night of music and song and we show up with our dancing shoes ready to party. It’s our way, for after all, we’re a musical people with a ready song on our tongue and a spring in our step. For Mesopotamian Night — Los Angeles (MN-LA), though, we can leave the shoes at the door and come in for an unforgettable musical experience.

The first annual MN-LA promises a feast of Assyrian music and song Saturday, May 30, at the Performing Arts Education Center in Calabases, California. The red carpet starts at 5 p.m., where you can renew acquaintances, enjoy refreshments and also bid in the silent auction. The concert starts at 7 p.m.

This is a big production with the Mesopotamian Night Symphony Orchestra, soloists and chorus led by John Kendal Bailey, the American conductor with an Assyrian musical heart.

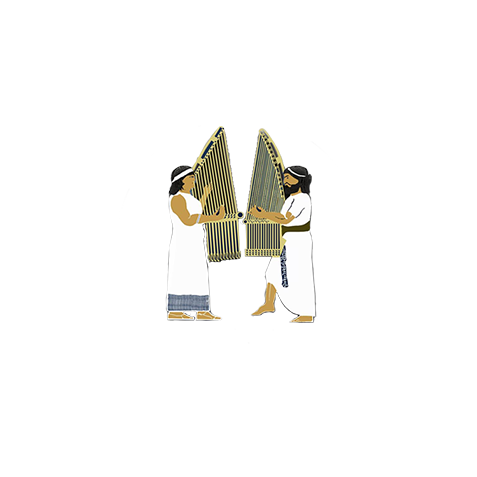

You’ll find the great traditional music sharing the stage with new works by today’s talented composers and performers, proof that we Assyrians have held on to the artistic flair of our ancient Mesopotamian civilization. Despite the Assyrian Genocide of 1915, and all the other crimes committed against our peaceful people through the centuries, we’re still here and ready to break into song.

And break into song she will, the versatile Assyrian singer, instrumentalist and composer Rachel Thomas. I first saw Rachel last year at the Mesopotamian Night — Chicago production, where I was master of ceremonies, and was impressed with her magnetic stage presence and intimate, sultry voice. Rachel will open the program with the powerful song “Cuneiform Graffiti,” composed by Rachel herself and orchestrated by Edwin Elieh.

It’s hard to listen to the song “Kharabid Nineveh” (“Ruins of Nineveh”) and not get a lump in one’s throat. “Kharabid Nineveh,” a tender and longing song, was composed by Belis Daniel, with the lyrics by Yousip Jacob, and arranged and orchestrated by the Rev. Samuel Khangaldy, a composer in his own right. Maryam Kouchari, who sang with the Assyrian National Choir of Iran, will perform.

The Assyrian Genocide Suite for Choir and Orchestra, composed and orchestrated by Edwin Elieh after the poem by Yousib Bet Yousib, commemorates the suffering of the Assyrians in the early days of the 20th century. Rabi Yousib based his poem on the diaries of Christian missionaries and others who witnessed the aftermath of the 1915 Assyrian Genocide.

Elieh set the composition in four movements. Black Winter opens the suite with an idyllic scene in Urmia. The second movement, Death Order, sweeps across the Assyrian villages and towns in the Middle East with a bloody picture of death and destruction by anti-Christian forces. The third movement, Torturous Migration, shadows the Assyrians escaping to freedom and re-settling in places far from home. The fourth movement, Endless Escape, serves as a poignant reminder, in view of the current barbarism against our people in the Middle East, that the 1915 Assyrian Genocide is in its second century and with no end in sight.

Tanahang, a Duet of Body & Piano, by Honibal Yousef, is a film of an open-air concert held outside Tehran’s Theatre Shahr (City Theatre), in September 2014, by the composer at the piano, with an incredible dance performance by Yaser Khaseb. Honibal incorporates music by the legendary Assyrian musician and composer Sooren Alexander. Tanahang, translated from Farsi as Duet of Body and Song, at times is peaceful and idyllic before exploding into jagged and distorted body movements, with the music turning abstract and atonal. Several themes run through Tanahang, predominantly one that paints the life of the Assyrians and other Christians suffering in the sectarian violence in the Middle East. The duet concludes the concert’s first half that commemorates the 1915 Assyrian Genocide.

After intermission, the second half opens with a short documentary that is a moving portrayal of Assyrians in Khabour, Syria, trying to survive the religious crimes against them. Sargon Saadi, the filmmaker, is an exceptionally talented and daring young Assyrian whose art and dedication to our people will make every Assyrian proud. The documentary is also the perfect lead-in for the live art auction, with the proceeds going to the Assyrian Aid Society of America to help Assyrians in need in Syria and Iraq.

The operetta Taliboota (The Marriage Contract), by the Rev. Khangaldy, flips the mood with a charming dose of Assyrian humor. The Rev. Khangaldy set the operetta to the song of the same name by another legendary Assyrian, the writer, composer and musician William Daniel. Modern Assyrian literature embodies a varied treasure of works by Rabi Daniel. Some of these compositions were written as musical poems, among them the little gem “Taliboota,” published in 1944.

“I really liked the poem and found it interesting and hilarious,” said the Rev. Khangaldy. “The original melody is very short, only five lines and twenty measures.” He subsequently expanded the poem with additional dialogue and musical variation into a delightful piece of Assyrian comedy recalling Gilbert and Sullivan’s British operettas.

Taliboota takes place in an Assyrian village where the parents follow the colorful ritual of arranging their children’s marriage. William Daniel had an uncanny flair for drama as well as comedy and all that is wrapped up into this hilarious operetta. At the same time, Taliboota has created controversy for its attitude toward women. In the story, the girl’s father likens her to a slipper, a savoolta, telling his future son-in-law to wear it and step on his bride if she is disobedient. He also reminds the boy that he has the right to give his disobedient wife a few whacks with his cane. “Women may not like to hear of this attitude toward them, but that’s how it was in those days and I did not want to change Rabi Daniel’s poem,” said the Rev. Khangaldy. For instance, he noted, that an Australian production of Taliboota changed the storyline by likening the young bride to a rose instead of a slipper. “I thought that ruined Rabi Daniel’s poem,” he said.

“The perception about the operetta Taliboota is wrong among our people,” added MN-LA Program Director Marodin Thomas-zadeh. “In the song, Rabi Daniel actually criticized the traditional culture and attitude toward women in the Assyrian community.” Despite the controversy, Taliboota is a joyous bit of Assyrian musical theatre that is sure to send the crowd home whistling.

Rachel Thomas returns to the stage with “Ishtary,” a sweet song about an Assyrian girl named Ishtar, composed in 1977 by singer David Esha. Rachel follows with “Nishra d’Tkhoumeh” (The Eagle of Khumeh), a tender and heartfelt nationalistic song, composed in 1917, by the legendary Assyrian Dr. Freydoon Atouraya. “Nishra d’Tkhoumeh always reminds me that I am an Assyrian heart and soul — an Atouraya. I have heard Rachel perform this memorable song and she mesmerizes.

Ogin Bet Samo will close the concert with a set of three patriotic songs, “Foreigner,” “Chee Bayennakh” and “Lenwa Bispara,” plus the rousing finale “Atta’d Ashurayeh” (Flag of Assyrians). Ogin, who hails from Kirkuk, Iraq, grew up in a musical family. The legendary singers Edward Yosep (Biba), David Esha and Ashur Bet Sargis, among a few others, were considerable influence on his growth and development as a musician and singer. Ogin credits David Esha, especially, with the most impact on his career by teaching him about the allegiance to one’s nation through patriotic songs.

The Atourayeh journey has been bittersweet. For centuries we have suffered cruelty and genocide in the name of religion. And that evil still plagues us in the Middle East at the hands of those with dead souls. Yet in all that time we have kept our faith and never forgotten who we are and where we come from. Most of all,

we have never forgotten our laughter — and always kept a song on our tongue.

The first annual MN-LA is a sweet reminder of that.