I first heard Rev. Samuel Khangaldy’s music at the 2009 Mesopotamian Nights production. It was the overture from the oratorio Gilgamesh and it was good stuff. The overture, about 15 minutes or so long, uses long and luscious lines in the tradition of the great symphonic poems by Tchaikovsky, Smetana, Liszt and Sibelius. “Surprise is the greatest gift which life can grant us,” said Boris Pasternak, and the Rev. Khangaldy’s music was such a gift.

I looked for the opportunity to chat with him about his musical world. The Rev. Khangaldy’s music is showcased in this year’s Mesopotamian Nights production with several compositions, so what better opportunity for a conversation? Here are some of the things we chatted about on the phone, since he lives in San Jose and I in Wisconsin.

Obelit: Your music is spotlighted in this year’s production of Mesopotamian Nights program. Music by another extraordinary Assyrian composer, George Somi, is also on tap this year. What’s your assessment of this year’s overall production?

Samuel: I think this will be a new experience for the audience by offering a completely different view of the choir combined with the orchestra. Also, the arrangements by George Somi and others add to the variety of the music. The different arrangements and musical styles, from classical to pop, especially the nationalistic songs, will make for a really exciting and wonderful evening.

Obelit: You had your first music lesson at age eight. And here you are, decades later, your compositions performed everywhere. Somewhere along in your life, did you have a sense of where you would be at this stage in your artistic life?

Samuel: I could not imagine this day, but I wanted to be a good composer. I liked classical music since I was a kid, and even though my beginning lessons were in Persian pop music, I always listened to classical radio.

Obelit: Music seems to permeate your life. What is music to you?

Samuel: To me, music is life, and as a Christian and a pastor, I believe salvation is the greatest gift from God to us and I feel that music is second to that. Music is the greatest gift from God after salvation.

Obelit: Are you a composer who writes Assyrian music or an Assyrian who composes music? Do you see a difference, and if so, which are you? Or does it make a difference in the artist’s life and work?

Samuel: I write music as an Assyrian, but naturally I was influenced by the environment in which I grew up — with a taste of Persian, Arabic, and definitely western classical music because it was my life.

Obelit: Upon reflection, how do you assess your development as musician and composer?

Samuel: I am never content with what I am doing. I like it, but I see that there is always room to be better and to develop. I had good teachers and I learned a lot, but I’m never satisfied. I want my music today to be different than it was last year, and the year before. I’m always ready to learn more from different composers, past and present, and even the great classical composers.

Obelit: You were born in Tehran and received a degree in economics from the National University of Iran. At the same time you were studying piano and music. Tehran Symphony Orchestra as well as the National Iranian Radio and Television Orchestra performed your music. You directed performances of choral works for the late Shah of Iran. Those are major accomplishments. Did you have a set direction for your life at that time or did you feel pulled in all directions by these distinctly different fields of study?

Samuel: No, at the time I looked at these as just special events. I never thought that today I would be in this position, providing music for my community.

Obelit: At the time, then, we could say music was just a sideline for you, whereas your main focus was on your economic studies.

Samuel: Yes, at the time my focus was on a degree in economics, but, at the same time, I was telling myself, “Why am I wasting my time here? Why am I not studying music?” In those days, living in Iran, the mindset was different. You became a doctor, an engineer, an architect, and music was not thought of as highly as it is today. Yes, I was studying music on the side, but now I wish I had studied music full time from childhood and thought of it as my profession.

Obelit: If I remember, back then if you were not a doctor, an engineer, an architect or someone with a tangible career, you were nobody.

Samuel: Some people considered music as a good hobby. Others said, “Well, we already have records to listen to and musicians and singers, so why do you want to waste your time on music?” Some people did not look at music as a respectable profession.

Obelit: As an Assyrian, did you face any obstacles, artistic, social and political, in those early years?

Samuel: No, not really.

Obelit: So then many avenues were open to you and that no one blocked your way.

Samuel: Actually I was respected, because I served the church with my musical talent. I taught music to Assyrian children as well as Persian. As a teacher, I was respected. As a Christian who served the Lord with my music, I was respected. So altogether I was happy with what was happening with my life.

Obelit: As a classically trained musician and composer, when writing and performing Assyrian music, do you feel the classical influence in your work? Are Bach and Beethoven looking over your shoulder? Is Mozart? Brahms? Tchaikovsky?

Samuel: I try to be myself, because everything I do comes from my nature, from the depths of my feeling and my heart. But of course, I cannot deny the presence of these composers in my life. I feel a little bit of each in me.

Obelit: Do you feel drawn to a specific composer from western classical music, or have a particular relationship, say, with Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms or the other greats?

Samuel: I like Beethoven’s influence. I like the rush, the intensity in his music. I like that kind of music — powerful and fast and intense. When you listen to Beethoven, you know it’s different from the other composers. On the other hand, I like the spirituality in Bach’s music, and sometimes I show it in my music.

Obelit: What about some of the other great composers?

Samuel: I like the poetry in Chopin. Sometimes you can hear it in my piano compositions. I like the freedom in Camille Saint-Saens. Even though he was French, he freely used African and Middle Eastern melodies and themes in his music.

Obelit: Oh, yes, a good example is the fifth piano concerto by Saint- Saens, titled “Egyptian.” One clearly hears those themes in it. The Fantasy for Piano and Orchestra, titled “Africa,” in which Saint-Saens uses Nubian themes and folk songs. He is a fascinating composer, and I know what you mean by the freedom in his music.

Samuel: Yes, of course. I ask myself, “Why can’t I do that?” Because I feel the same freedom to use melodies that are not Assyrian — I mean in spirit. After all, music is the universal language and I feel completely free to use whatever I want.

Obelit: What are your thoughts about Assyrian music arranged and performed for western-style chamber ensembles and big orchestras? Mesopotamian Nights productions have been a major force in presenting Assyrian works in symphonic and operatic forms.

Samuel: I take that as a big step forward in Assyrian music. One thing I know about Persian traditional music is that it’s not developed because they think of it in simple arrangements. Now that Assyrian composers are embracing the western style of music in broad terms, it is opening new doors. I see that our music is so rich that our composers can produce it in great orchestral works.

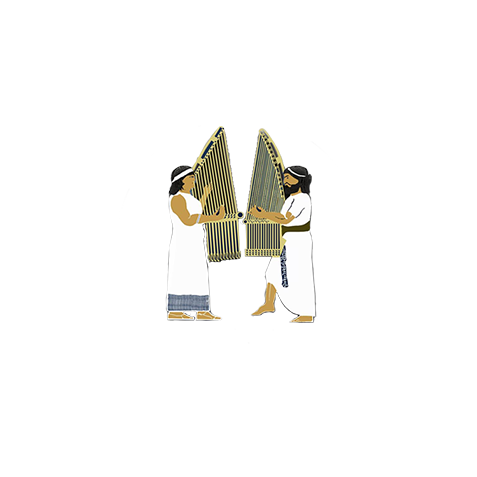

Obelit: I have read some sniping against Assyrian music being arranged and orchestrated for western-style ensembles: that this detracts from the “purity” of Assyrian music. I find the comments absurd. What does “purity” mean? Does that mean we’re stuck forever with the zoorna and the davoola, that we have to limit ourselves to the musical instruments of our forefathers, and that we are not creative enough, visionary enough to explore other performance medium

Samuel: In this year’s Mesopotamian Nights program you will hear how beautifully Assyrian classical melodies are arranged and orchestrated for a big symphony orchestra. George Somi does a beautiful job by bringing in the zoorna and the davoola in the symphony orchestra. That shows you that you can use simple Assyrian instruments in the big orchestra. It’s world music and you can do anything you want without any obstacles and nobody can limit you. It’s an unlimited musical world.

Obelit: You immigrated to the U.S., in 1984, with your family and settled in San Jose, California. Later you received a degree in theology from San Jose Christian College — later changed to William Jessup University — and were ordained in 1996. Currently you’re the associate pastor at the Assyrian Evangelical Church of San Jose and the Bay Area. Does religion influence your music?

Samuel: Yes, of course.

Obelit: How so?

Samuel: I mentioned that to me music is the greatest gift from God after salvation. I started with church music and as a kid played piano in church. I look at God as a great musician and artist. If a string on a wooden box creates music by vibration, that’s the nature God put in that string and the wooden box. We hear music in birds and in nature. So, yes, God is a great musician and He inspires me. God has given me musical talent and I try to glorify Him with it.

Obelit: You’ve composed orchestral music, choral, solo, especially for the piano, Gospel, Assyrian folk dances. Is there a particular medium you prefer?

Samuel: I like the whole thing. Everything. Every style. For instance, piano solo is the best way to express my feelings when I am alone. I sit at the piano and my fingers run on the keys, creating something I never thought to create. Music seems to come by itself without my thinking. That’s internal feeling. It comes from deep within me. I cannot do that immediately with the orchestra. The piano is the first and the best instrument for me to express my internal feeling. And then, if necessary, I can transcribe it for a big orchestra.

Obelit: Early on, in Iran, you switched from the accordion to the piano. What compelled you to make the switch?

Samuel: I played according for three years and pretended it was the piano — I would sit on the floor with the according keyboard on my lap horizontally and play it like a piano. I was invited to play the accordion in school many times, but I didn’t like to do that. So then when my father suggested we sell the accordion and buy a piano, I could not be happier and my answer was a big yes. We sold the according and bought a piano — the only piano available in town.

Obelit: Do you compose at the piano? Who was it, Stravinsky, who composed at the piano standing up?

Samuel: Sometimes at the piano and sometimes on the electronic keyboard. Sometimes, when I don’t have an instrument, while driving or in bed, I hear the music and the instrument that can produce that feeling better. For instance the oboe. Or should it be a violin or a trumpet? Whatever instrument comes to mind and that I feel fits.

Obelit: Do you compose when time allows or devote a regular time to it

Samuel: No, I don’t have set hours to compose. I’m a pastor and have to be available anytime that the church needs me, or people need me. I also teach piano. I am occupied with so many things and I have to make time for them. So I do music between jobs. I compose whenever time allows, but mostly in late evening.

Obelit: Do you need inspiration to compose? Or do you have a specific method to get the creative juices flowing? For instance, Brahms said he got some of his best musical ideas while polishing his shoes in the morning?

Samuel: I am in love with music, with life, with my family and with nature. I’m also in love with my Assyrian heritage. I find inspiration everywhere. There are moments when you can feel inspiration is more dominant, but there is always something to inspire me.

Obelit: What role does Assyrian nationalism play in your music?

Samuel: I love my nation and am proud to be an Assyrian. I have always wanted to write music on Assyrian themes — Gilgamesh, Ishtar going to the underworld, even the persecution of Assyrians during the genocide. I love Assyrian mythology. I love the mythology from other nations, as well, but Assyrian mythology has a special place in my heart and mind. The Assyrian nationality and music have a special place in my life.

Obelit: Nationalism, love of our heritage as Assyrians, runs in our blood. Wherever we go we’re Assyrians first. This nationalism also is present in every bit of music we hear by Assyrian composers. And rightly so, I might add. It’s been the case for just about all our composers of the past. Do you find it so in our contemporary composers?

Samuel: Yes, I hear that in them.

Obelit: What is your assessment of our past composers?

Samuel: Nobody can give everything, but each gave something to our nation. Paulus Khofri gave something to Assyrians. So did William Daniel. Nebu Issabey gave something that William Daniel didn’t. William Daniel gave something that Nebu Issabey didn’t. We are fortunate to have had these composers, and others, because each left us a musical treasure.

Obelit: I don’t mean to put you on the spot, but what is your assessment of our contemporary composers?

Samuel: Prior to 2008, when Mesopotamian Nights premiered, I could not imagine we had so many good composers and arrangers. When these programs started, I realized how many talented musicians we have, and they’re all awesome to me.

Obelit: Do you see any particularly bright stars among our contemporary composers?

Samuel: It’s hard to answer that. But I see one or two of them that can really shine in the future if supported by Assyrians. I like George Somi.

Obelit: Yes, Somi is a remarkable young Assyrian composer.

Samuel: Also there is another composer and musician — Rasson Bet-Yonan. I have never met him, but I have heard his music. When I heard his piano music and his Variations on Assyrian Folk Music, I was amazed.

Obelit: I wrote the jacket notes for his CD Theme and Variation in Four Movements. He really impressed me, too. A lot of the Rachmaninoff in his music. It blends beautifully with Assyrian.

Samuel: Yes, he is really something.

Obelit: He and George Somi are bright stars. Tell me, once upon a time Assyria dazzled the known world with its culture, art and architecture. Perhaps even music. Do you see that, or even get a hint of it, in us, the Assyrians of today? Will we dazzle the world with our serious music?

Samuel: I don’t know. If it happens, it will be in the far distance. Most nations have had centuries of musical heritage and background. They have had great composers and millions of musical creations. Assyrians are new in this particular world of music and have very little experience. If I may say so, also little education compared to the great composers of the past, and even contemporary musicians. We don’t even have music performers — instrumentalists, I mean — to shine on an international level. On the other hand, there is big competition in music around the world, and there are politics involved. You have to show yourself among many musicians from many countries. Reaching that level, when we will dazzle the world, would be tough. I wish that happens someday, but I don’t see it in the near future.

Obelit: Upon reflecting on our music — of the past, of today and of the future — where are we? Where have we been, where are we, and where are we going?

Samuel: I think we are making good progress. Yesterday we were better than fifty years ago. Today we are better than yesterday. Our composers are growing at a great speed — many of them are active and helping in Mesopotamian Nights. And there are a many more we don’t know about. We now have so many more musicians than we did in the past, especially educated musicians, that I see a bright future for our music. Yes, yes, today we are much better compared to the past.

Obelit: What lies ahead for you? Are you working on anything special, a big Assyrian symphony, an opera or a choral piece?

Samuel: This year I was very involved with Mesopotamian Nights. Two pieces in the program are my original melodies and orchestrations, and the others pieces by other composers that I have orchestrated. The big work that I started four years ago, Gilgamesh, I stopped that year. I want to start working on that once again, if time allows, if God allows, and to leave a legacy behind.

Obelit: Any other compositions?

Samuel: I am working on two projects. One is some piano music that I composed years ago that I want to publish. The other is church songs, some sixty or seventy of them that I want to put in a different book.

Obelit: Do you have a message for our artists, young and old: writers, poets, composers, musicians, painters, dancers, and so on?

Samuel: Art in general is a beautiful thing. It’s a great gift to humanity. Everybody needs that, from the young to the old. Life is not all work. Being sensitive with artistic feelings makes us more sensitive to the needs of others, sharing more love and music so that we can understand each other. Everybody needs that. So my message to Assyrian families is to please encourage children to learn an instrument, not necessarily to become musicians, but to at least be a friend of music and to understand music. Our community needs to have that.

Obelit: You can add literature to that. And, yes, poetry. Theater. Art and sculpture. Dance. Opera. There is no limit to the arts. You yourself are also a fine calligrapher. And a painter. Mostly in oils. It’s easy to see the love of God and nature in your landscapes.

Samuel: If you as parents see that your children have a special talent in music and writing and theater and dance, encourage them. We need that. Don’t force them to do the things that they don’t want to. Assyrians have had great influence in history. Why not now?

Obelit: And perhaps out of all this we’ll see future Assyrian composers.

Samuel: We can only hope and pray.