The story of “Badri” the little eleven years old Assyrian girl, who witnessed the exodus of her people from Urmi on the eve of July 18, 1918, is coming to life on stage at the Caliornia Theatre in San Jose, CA, on August 1, 2015. This Assyrian literature masterpiece was created by the late John Alkhas.

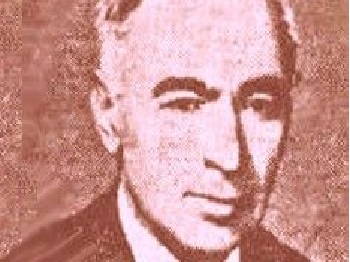

About John Alkhas

The late John Alkhas was born in city of Urmi, Iran in 1908. He studied in Catholic missions in Tehran and Tabriz. In 1926 he left for India and expanded his education and literary knowledge. In 1948 in Tehran he established Assyrian printing capabilities and in 1952 along his brother Addai Alkhas founded the Assyrian printing press of Khooneen and published the Assyrian magazine Gilgamesh.

Most of John Alkhas contribution to Assyrian literature has been through poetry. He is recognized as the best Assyrian poet of 20th century and mostly is known as the Poet in Exile. “The Badri Tragedy” is one of his handful prose writings which has received many reviews, and republications

The Tragedy of Badri

By John Alkhas

Translated by Dr. Arianne Ishaya

Introductory Note:

By Daniel David Bet Benyamin (translated and abridged by A. Ishaya)

Mr. John Alkhas, an eminent Assyrian writer and poet, wrote the “Tragedy of Badri” based on the events that took place on Thursday, July 18, 1918, on the plain of Urmia.[1]

Three years prior to that the Assyrians from the Highlands of Hakkari, having come under the attack of neighboring tribes, had fled from their homes and were living as temporary guests of the Assyrians of Urmia.

To clarify the mind-set of this group of Assyrians at that time, it is necessary to mention that since the mid-1800s, European and American Christian missionaries had established mission schools in the region. Consequently, Assyrians became literate in several languages and learned about their ancient history through books and periodicals that were published in Urmia by local educated Assyrians.For the first time the Assyrians discovered they were descendants of a great nation with a glorious history. Along with the local authors, there were Assyrian scholars who were educated in foreign countries and upon their return, awakened the spirit of

nationalism among fellow Assyrians.

This spirit of nationalism sparked hope in the heart of the young and old alike. They began to nurture the idea that, in the near future, they would return to their homeland to live as a sovereign nation. What they didn’t know was that their enemies were secretly plotting obstacles to prevent them from ever attaining their goal. Overnight their dreams were dashed and their hope of becoming a sovereign nation was lost.

On that fated day, John Alkhas was just 11 years old. He was not old enough to have written down the events of that ominous day as they happened, with the level of artistry and literary expertise contained in them. But the description of events is so vivid that we can only assume John was standing next to little Badrias she stood on top of that calvary [hillside].

On that day our people faced one of the worst calamities in their history. John has skillfully sketched those torturous events in the Tragedy of Badri. Even though the account is written in prose, elements of poetic style such as rhythm and rhyme are present

in some of the passages.

Let us now turn to the “Tragedy of Badri”

The Tragedy of Badri

Oh

daya [mother],……OhShimun,……Oh brother,……Oh Laya,……..

These were sounds of despair uttered by young lads and maidens in long-drawn out syllables, in sobbing voices heard separately, heard collectively, heard from everywhere in the surrounding hills of a dark Tamuz [July] night.

Mingled with the responses of the parents who were present, were the sounds of bleating sheep, neighing horses, bellowing cattle,coming from a small meadow alongside a wide road where the smoke of burnt straw, and the smell of roasting flour clouded the presence of small children crying, the disabled groaning, the wounded complaining; of children mourning over their dead parents and of parents lamenting the loss of their children.

The sounds of pandemonium [chaos] burst into the sky; but the sky was unmoved. It hid its face behind a thick, black fog.

There, on the side of the road, in the cleft of a high cliff, Badri, only 12 stood motionless as a stone statue staring at the movements of people, animals, and carts that looked like a moving stream leaving behind the old and worn out men and women; the sick, the abandoned children, pregnant women, carpets, household furnishings, food, exhausted animals……..

A human stream on the move, not knowing for how long, not knowing where, all day long it moved, and all night long it flowed. Sometimes well-equipped they went, and sometimes protected they went. Each went on his own; all went collectively. Without a guide they went; without a supporter they went; without a leader, without being led, without a set time and hour they went. With no thought of survivors, with no thought of the dead, with an empty heart, with a resolute intent, they walked. With no clothes or shoes they walked; toward a clear goal they walked; always forward they walked.

From all the unburied dead; all those abandoned without protection; from the bound soldiers, from everything left behind broken,their heavy hearts heard this urging:

“Leave me and go; cut me loose and go, flee and go, do not delay and go.”

For the cause of liberation, for this vision, for this new awareness, this urging on, they were walking; they were flying. Hungry, unaware of the loads of wheat and grain, without laying a hand on the abandoned cattle, sucking on wet mud to quench their thirst, without wasting time, they rushed on……

To lighten their headgear, to cool their back, to rest their feet, they cast away woolen hats, expensive clothing, and their leather shoes. They wrapped their feet in straps of burlap; they left their head bear, and covered their bodies in light shirts.

The perilous risks they took were not to save their lives. They knew well that if Shimun was to be renamed Kassim, and Martha Zeinab, no bodily harm would come to them. It was not for the sake of their personal lives that these self-sacrificing Assyrians were climbing the hill. Their exodus was not aimed at dispersion in different countries to be enslaved by various nations for the sake of a loaf of bread.

No!

They had chosen a single path in order to return back and reaffirm their identity as a people.

They were not going on their own volition. They were driven as by hidden arms. They were being pushed by the hands of the self-sacrificing Assyrians; by the spirit of their national martyrs.

Among them were those who had slowed down. Weeping quietly, they stopped and looked longingly on those who were abandoned by the roadside. Then crazed with anguish, they hurried on to catch up with the advancing convoy.

They all had a single thought: to preserve at least a remnant of the Assyrian nation in the hope of safe-guarding its identity, and salvaging its language. So onward they walked in order not to lose their heritage, that sweet and sad legacy which their forefathers had guarded for 26 centuries amid fire, massacres, turmoil and upheavals.Inspired by the prospect of freedom, they were also fulfilling their duty. These free spirits, rising from the depths of the sea, had broken the yoke of bondage. They were escaping the shackles of enslavement. They were hurrying away without looking at others. Each on his own, all as one.They were climbing, clutching at this sorrow-filled Calvary [hillside] in the sacred hope of the future, a very near future when they would taste emancipation for their people, their language, their religion, and for their heritage.

This sacred prospect had blinded them. Therefore, they did not see; they did not feel; they did not take stock of their suffering. As if sleep-walking, they were breathlessly marching towards the allurement that pulled them forward. At every step their gaze was fixed on the banner of freedom carried by their clergy, preachers, and bishops.

With no fear, no trembling, in their own language, relying on no one else, they declared their pride in the Assyrian power, their churches, and the Assyrian towns. They paid homage to the Assyrian martyrs who had given their lives on that Calvary. So every year, in the month of Tamuz [July] they commemorate the Tamuz Day instead of the Rogationof Ninevites. They burn incense, light candles, prepare food, and pour out drinks. They spread petals on the graves of the past martyrs, the martyrs of ages, the martyrs of all time.

Poor Souls!

Instead of this pleasant vision, if they could only see, in the midst of this mirage, the great numbers who not only forgot this drama, not only ignored the wounds, the graves of their forefathers, their heritage, their people, their legacy, but also their language. If they could only see how some would attempt to destroy the church, and to slander the clergy. If they could see that a great number would speak and pray in foreign languages, debasing and disowning their own mother tongue, if they knew that some, after being saved from this tribulation, would throw themselves into the nothingness of foreign nations singing;

“Lift your head from the grave Witness the outcome of your aspirations You, who sacrificed your life for Umta, [nation] Alas! How futile was the loss of your life!”

If they had seen the outcome while they were in the midst of that mirage, if they could recognize these betrayers, these individuals, for certain they would have trampled them under their feet that bled from piercing thorns, sliced by swords and rocks, caked as they walked on burning earth. If they only knew, they would have strangled the life out of them while they were still in their cradles.

But since during those turbulent times they were not thinking, they could not foresee that after this ordeal, after this hell, after the ultimate sacrifice, they would find some who would betray the cause; they would stray from the path that was to rebuild the ruined Assyrian churches, restore the Assyrian schools, and everything Assyrian.

To return free, prosper as free men, grow and live as free people was their resolve. If not, better to die free, rather than live as slaves of another nation, lose the mother tongue, dishonor one’s heritage, deny one’s identity, abandon the graves of their forefathers and martyrs, and all those who died for their nation and religion.

For this reason, eyes fixed on the horizon, they moved forward resolutely without taking stalk of the surroundings, without feelings for the ones they left behind, without sorrow for scattered household belongings, without knowing if they would reach the end, or when they would collapse upon the slopes of this Calvary.

Forward went these warriors of freedom, these rebels against slavery, these lion cubs of Assyria, these virgins of Ishtar. They walked light-footed, yet with a heavy heart on an empty stomach and dry mouth. How long did they walk this way?

When the last of them passed by, it seemed that the ground rested for a while. Then as if a wave had risen, all those who had collapsed came to themselves. With a last effort they stirred up; the bent-over old men and women, the wounded and the sick started crawling, pushing themselves on the ground while they implored God to save them from the hand of the enemy. In jolting steps they walked as if there was hope in every step; they trotted in agony. Then, one by one, they fell. They lay quiet. As they took their last breath, they hoped that they would remain alive forever in the memory of those who survived; in the memory of generations to come, in the annals of the history of their people.

Badri was still standing in the cleft of the rock. The only sign of life in her was the bulging eyes staring at the crowd that was slowly disappearing from her sight. She had not seen her parents in the multitude. Had they already passed by without seeing her? Or, had they not yet arrived? What else was Badri expecting? Why was she not running to join the others? Was it because of exhaustion, hunger, thirst, or the fear of not finding her parents? All these causes kept her paralyzed. Only a tiny spark radiated through her thoughts and lightened her eyes: the hope of finding her loved ones!

[1] This is part I of the Tragedy of Badri. It was published in Gilgamish#14, 1953. At the end of this article the author, John Alkhas, notes that part II would be published in the following issue. But the sequel was never published. Nimrud Simono, the chief editor of Gilgamish wrote the following postscript:”The sequel to Badri was not published because it was too political. It is lost together with the rest of his manuscripts as well as those of his brother”. [Well-known author and poet, Addi Alkhas.]

Dr. Arianne Ishaya

Dr. Arianne Ishaya is a cultural anthropologist and a faculty member at the De Anza College in Cupertino, California. She has published several books and many article on the history of Assyrian immigrants in northern America and other topics.