Music: Michel Bosc

Poem: Yosip Bet Yosip

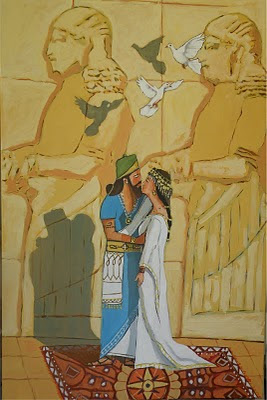

(painting: courtesy of Paul Batou, Los Angles)

The world knows her as Semiramis, Semiramide, Sammu-Rammat, Samira, Shamiram. To us, the Assyrians, she is simply Shamiram.

Numerous operas are based on this mythical Assyrian, including Semiramide by Domenico Cimarosa, Marcos Portugal, and, the most famous, Gioacchino Rossini. Now enter the cantata Ninos and Shamiram by the French composer Michel Bosc and the Assyrian poet Yosip Bet Yosip.

The cantata is among the highlights in this year’s Mesopotamian Night, a gala production of Assyrian classical and popular music with dance, on August 21, at the Gallo Center for the Arts in Modesto, California. In its fourth year, the Mesopotamian Night series is presented by the Assyrian Aid Society of America (AAS-A) not only to showcase the Assyrian classical and popular performing arts but also to raise funds through tickets and its art auction for needy Iraqi Assyrians.

Many myths and legends surround the beautiful and shrewd Babylonian princess who became the Assyrian queen. According to one legend, a shepherd found Shamiram, born in the desert and reared by doves. Some historical accounts of her later life note Shamiram married King Shamsi-Adad V (or VII), and after his death, she ruled for a short time, until Adad-nirari III (or IV) ascended the Assyrian throne.

Shamiram appears as queen and goddess in some Assyrian mythological accounts of her life, and that she was the daughter of the fish goddess. Not only was she the founder of Babylon, Shamiram also gets the dubious credit for inventing the chastity belt, and also for being the first to turn young boys into eunuchs by castrating them. According one legend, she married King Ninos, who founded Nineveh, and after his death, ruled for many years. Her end came at the hands of her son. Finally, the beautiful Shamiram turned into dove and flew away.

Somewhere between myth and reality lies the truth about Shamiram’s life. Either way, this remarkable and colorful Assyrian legend continues as an ideal subject for literary and operatic works. Rabi Yosip’s song-poem, Ninos and Shamiram is one such example, set to Bosc’s musical score.

Rabi Yosip’s Ninos and Shamiram had its origin in an Assyrian song-poem he had heard in his teens in Tehran. Sung by a friend named Nimrod, from a mountain village in Urmia, the story was part of the Assyrian oral tradition, passed on from one generation to the next. It told of an encounter in a lush valley in the mountains between a hunter and a shepherdess.

Both melody and poem were different from what they are now, recalls Rabi Yosip. The poem had Persian, Turkish and Kurdish mixed in with Assyrian. It had rhyme but no meter. “Some years later I reshaped and refined the poem to reflect our Assyrian culture,” he says. “I also re-shaped the melody to make it happier, more romantic and beautiful.”

In the following years, as he matured in age and his knowledge of Assyrian history grew, he revised and expanded the poem into a more literary work. He also made some changes in the melody. By then he had heard many myths about the legendary King Ninos, who had met a shepherdess in the dessert named Shamiram and made her his queen. Elements from all the stories, myths and legends about Ninos and Shamiram found their way in various forms into Rabi Yosip’s new version.

Finally he titled his song-poem Ninos and Shamiram, transposing the characters of King Ninos and Queen Shamiram into a young prince named Ninos and a beautiful shepherdess named Shamiram, who steals his heart and compels him to ask she go with him home to Nineveh.

“I will come with you,” she says, “for your love has pierced my heart, too.” When she asks who he is and where he comes from, he answers, “My name is Ninos, the son of the high priest Nahrin.” Shamiram tells him that he is not a hunter, but a shepherd like her. “I of flock,” she adds, “you of people.” Ninos asks, “Queen of beauty of these hills, what is your name?”

She was named after a dove, she explains, and goes on to tell the story of how a dove perched on her cradle, and that when it flew away, it left a small feather on her chest. She says she has kept the feather in the hope that someday it will lead her to the dove. “That is why they decided to call me Shamiram,” she says, “which means ‘A Name Exalted.’ ”

Rabi Yosip’s poetry soars with imagination, weaving myth and legend with historical data. Most of all, the words are those of an Assyrian poet whose love of his nation sparkles with the romantic imagery in the song-poem Ninos and Shamiram.

“Yosip Bet Yosip is one of our finest poets with a deep knowledge of our folkloric tradition,” says Tony Khoshaba, AAS-A Central Valley president and Mesopotamian Night producer. He points to the song-poem’s contrasting themes of a village girl’s simplicity in Shamiram and a prince’s urban sophistication in Ninos, and that the subject holds vast interest in any culture. He also feels Ninos and Shamiram was especially ripe for a Mesopotamian Night musical. “In general any love story tied to mythology makes an interesting story,” he explains, “but I let Michel decide whether it would be a good musical subject.”

Michel Bosc had already worked on previous year’s Mesopotamian Night production. One act from his opera Qateeni Gabbara was presented at the 2009 gala performance. Based on William Daniel’s Assyrian Epic, Qateeni Gabbara is still a work in progress.

Also for the 2009 production, Bosc had orchestrated solo piano works by the Assyrian composer Paulus Khofri into a suite titled Assyryt. The first part was presented in the 2009 concert as Assyryt Suite No. 1. Assyryt Suite No. 2 is in the lineup for this year’s program.

“I had confidence in Michel and in his commitment to deliver a superb work,” says Khoshaba. “He is a genuine artist whose work has a certain charisma. But I also think he liked the story.”

Ninos and Shamiram is written as a cantata for soprano and tenor with orchestra. The cantata, from the Italian word cantare, meaning “to sing,” was a relatively large 17th-century secular work in operatic style for one or two singers with accompaniment. It continued to evolve into a more elaborate work that included secular and religious texts.

Johann Sebastian Bach transformed the cantata to include soloists, chorus and orchestra, producing some 200 church cantatas. Since the late 18th century, the cantata has further evolved into a choral religious or secular work with orchestra and with or without soloists.

“I decided on a cantata in the baroque sense, with an overture and several movements,” Bosc points out. “It makes the story more intimate and the reading easier and clearer. It’s more operatic, too.”

To bring out the cantata’s colors and sensuality, he wanted a symphony orchestra with harp, harpsichord and celesta. To that, he added bells, cymbals, vibraphone and glockenspiel. Bosc explains he set out to create in the cantata something personal, since he already feels part of the Assyrian community. “Ninos and Shamiram is also universal,” he adds. “It begins with a real Assyrian theme, but the rest is mine.”

Bosc admits he was drawn to the story of Ninos and Shamiram. He especially saw beauty and magic in the character of Shamiram, that she is proud and free like the Assyrian soul. “I loved her at once,” he says, “and I decided to write for a high coloratura soprano, and to offer her a virtuoso piece.”

Ninos and Shamiram must reach beyond the Assyrian concert hall, Bosc notes. The world must discover it. Part of his plan to give the cantata a universal face is already in place: Ninos and Shamiram will be published in France. “This culture must be discovered and must travel,” he says. “I want every singer to be able to sing this Assyrian legend.”

Obelit Yadgar

Writer and Master of Ceremonies

www.obieyadgar.com